Not pieces, masterpieces

Our lives are much more fragmented, as a fundamental consequence of technology. One thing I have not explored yet is how that influences the artists (or creators) of the Internet.

When you think about the artistic works of the past, what comes to mind? Books, movies, paintings, architecture... You think about the masterpieces and the monuments, not the Picasso butt doodle.

What I see around the Internet, broadly speaking, are such doodles. One time, 10 minute attempts. They might be cute for 10 seconds and then you forget them. Crucially, they also lack an attribute that I want to highlight in this essay, an attribute most lacking in what is produced today, every day, is coherence.

To pieces

Let me give you a story to illustrate what I mean. I joined Twitter in 2015. Only in 2018 I began to go there more often, as a response to boredom, or to escape from work for a moment. I started to write Naval-esque tweets and threads. One fall Saturday morning, I commented on one of his posts and went to pick some apples. And when I came back, my world had changed forever - Naval retweeted me. Oh, the sweet rush. The flood of cheap dopamine. The invigorating engagement. My account rose from obscurity and I became a budding nano-influencer. This is the real beginning of the attention shredding process.

Soon after that fateful moment, I noticed that I started to check Twitter more and more. And as the coder that I am, I built a browser extension to see how often I check it. 100 times a day, 150 times a day, 200 times a day. That's not a number you want to go up. Alarmed, I set up limits that I still use to this day and blocked Twitter for most of the day. One of the best decisions I ever made. However, there was another decision I made soon after. No Twitter on Saturdays.

This is where it ties back. You see, after about 40 hours away from Twitter, I opened it again, and saw something curious. The posts seemed so... random. Now, I thought I "curated my following carefully" so why did the feed feel so irrelevant on Sunday afternoon when it felt so engaging on Friday evening? Most curiously, a couple hours later the feed seemed more interesting again and the sense of irrelevance and randomness faded. This experience serves to highlight how luring the jumble of various ideas in various media forms from various people around the globe is. It's exactly the sort of variety that our brain is hardwired to enjoy, despite the fact that the information is not useful to us.

It is no wonder that the habitual consumption of this random would-be relevant collection of other peoples would-be-helpful or -interesting thoughts would also lead to production of these random thoughts. Monkey see, monkey do. For most people, fortunately, this is akin to screaming into the void. I say fortunately, because the lack of feedback eventually makes people stop. And do something else. However, if the feedback is present, and one's random musings are rewarded with likes, it leads to further use and doing more of what made you feel good before. In this case, tweeting. That's how the platforms get us. And so, the creative effort is channeled towards making pieces, instead of coherent wholes.

Many people on Twitter have thousands or tens of thousands of tweets. Yet, if you asked them what they're proud of creating, they most likely wouldn't point to any one of those tweets. The tweets are produced as spontaneous shower thoughts, screams for attention, or a short-term means of getting followers.

As an Internet friend DB put it:

When you work at places that require periodic deliveries of content rather than individual pieces of good work, you end up with volume of videos but nothing specific to show off.

This is a general phenomenon. Instagram posts. YouTube videos. TikToks. These platforms incentivize the creation of "pieces of content." They lead to the production of likable soundbites. And if we, as creative people, fall for this, we become "content creators." Over time, these "pieces of content" become the only thing we create anymore because producing something else, something unique, something coherent and whole, that would actually require effort.

You see, creating a coherent whole requires 3 things—focus, vision, and synthesis—all of which are destroyed by social media.

Focus. How long can you focus? How long can you do 1 thing, fully concentrated? 5 minutes? 10? 15? 30? 60? 90? The length of attention span determines the kind of thing you can create. If you can only focus for 5 minutes, you can't write a chapter of a novel, but you can write a tweet. And isn't that better? After all, you don't get likes for writing a scene in a novel. But that's not the sinister part, the sinister part is that these platforms are designed to slowly erode your ability of focus like the wind erodes a rock spire on a prairie. Over time, they render you unable to create anything else besides their chosen format. And this profoundly limits the kinds of things that we create.

Vision. What is a vision? The word is thrown around too much. To me, it's simply about knowing what you want to create. Seeing it in your mind's eye. Imagining the scene in a novel, the web app interface, the groove of the song,... That's when the lack of focus also comes into play. If we imagine an extremely ambitious work of art, but don't trust our ability to focus for long enough to make headway, we'll become less ambitious. We'll set our eyes on simpler, smaller things, dreaming of one day making the masterpiece we imagine, instead of chipping away at it patiently every day. So we edit and chop down the things we want to create before we even explore them fully in our imagination.

Synthesis. The other problem with even arriving at any sort of artistic vision is that it takes time, specifically, time spent synthesizing—mulling things over, shuffling ideas around, exploring interesting what-ifs... And this doesn't happen when we fill every minute and every hour with checking whether a tweet did well.

Focus. Vision. Synthesis. That's what creating a coherent whole requires. We'll return to these elements later.

Now, it seems to me that every day, we have some time to create things. Some people have more, some less. And with that time, we can choose to write a 100 tweets, or a third of an essay, or a 1/1000 of a book. But not all of those. And it seems to me that it makes more sense to focus our efforts on complex and ambitious tasks, not the simplest ones. If you want to become an essayist, should you not first and foremost work on the essays, instead of writing tweets about writing, or not writing (as seems to be the case with many "aspiring Twitter authors")? Our skills tend to lag behind our ambitions, and if those are already set low...

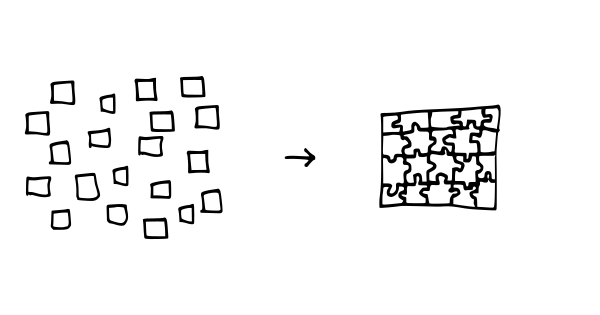

You could say that you can turn the tweets into an essay and the essay into a book, and that is true. However, this often results in a sort of loose collection. A pile of things that the consumer needs to sort through. Besides, few people successfully incorporate the short-form pieces into a long-form whole, because that would require precisely the kind of effort for which they don't have enough focus: the effort of integration.

Integration

Right now, I'm in the middle of two work projects that both require a lot of integration, one of writing and the other of software. And it's difficult. It's difficult because of the complexity involved in the task. You have a section here, a section there, and a section over there, and each section has subsections that emphasize certain ideas. Those ideas need to form a coherent whole, because if they don't fit, then you'll be left with that random collection of loosely related ideas that don't build on one another, don't resonate, and don't lead to change (like Twitter, for example).

Since I'm in this process of integrating parts into a whole, I can understand why many people never do it. You have to figure out what the right pieces are and load them in your short-term memory to be able to manipulate them in your mind. You need to understand what you're trying to do and whether the individual ideas or components support or detract from the whole, build resonance or destroy it. And you need to make a thousand little changes to make the ideas connect, instead of being slapped together. All this takes a lot of sustained attention, focus, synthesis, and vision.

And these are exactly the abilities that most people who go down the "content creation" rabbit hole lose in that process. Episodes, atomic essays, tweets, posts... All just pieces, no whole in sight. They might be even good pieces, but they remain far inferior to what a whole created out of those integrated pieces might be.

Why wholes

As I said above, integration requires effort. You might be asking: why make the effort? Why bother? It's easier to write 100 tweets than to write 5 interlocking chapters of cohesive prose, fictional or not.

First, consider this question:

When your grandchildren ask you how you spent your time, what will you say?

"I wrote 10 000 tweets." "I built an audience."

To me, that just seems thoroughly uninspiring.

Second, you hear a lot about competition. About the battle for attention and eyeballs. This kind of framing makes reality seem zero-sum. Fortunately, it's not the only framing, and even if you do believe it there are ways to escape this eyeball competition.

Here's a tweet from Naval on the topic that is now widely circulated around the Internet:

Escape competition through authenticity.

Like many tweets, it does have a point, but it's so generalized and lacking in context that it's not that useful. Once again, I'd argue that this is a case of the medium defeating the message. But anyway.

Say you see that tweet and think: that's interesting. Now the question is: what is authenticity? How does one become more authentic? I think these sorts of questions often throw people in a bind. They put the focus on the I. Am I authentic? How can I be more authentic? I questions can become existential, and tend to make people even more self-obsessed than they already are.

I think it's better to steer the conversation towards the work:

Escape competition through integration.

For reasons mentioned above, many people lack the attention span needed to produce integrated works of art. Creating wholes requires keeping context available in your mind in order to connect ideas in a way that builds resonance, and that leads to something bigger than the sum of its parts.

To understand what I mean, look at Twitter as a counter-point. Most tweets don't build on one another. Random idea #1, random idea #2, #3... There is no coherence. No resonance. No single tweet makes you pause, rethink your life, and change. A good piece of long-form writing, however, has a much higher chance of doing that. Long, old-school blog posts and books can have a huge impact on an individual. And this is the opportunity that is available to any creative person today: because most people focus on the pieces (posts on social media, mainly), focusing on the whole will distinguish you.

Because I like fantasy, Brandon Sanderson's work comes to mind. Sanderson just made Kickstarter history with the #1 most-backed campaign. Now, there's many reasons why Sanderson succeeded (some luck, finishing the Wheel of Time after the late Robert Jordan, following in the wake of Harry Potter and Game of Thrones), however, the one I want to highlight is the creation of Cosmere. As Sanderson puts it, it's the Marvel Cinematic Universe before MCU came about. What this means is that while his books are self-contained stories and series, they are all part of the same universe, and there are connections that a reader can make from one book to another. There's a shared timeline for Cosmere books that you get glimpses of in the individual works. Sanderson has a 35 book plan for Cosmere, and he's building it bit by bit, book by book. And when you start reading his books, and you learn about the connections, you want to read all his other works and series. You want to solve the puzzle of the Cosmere.

This is not the case for most authors. Most authors struggle with getting their readers to read another series of theirs. By establishing a shared framework between the individual stories, Sanderson fans (like me) feel compelled to read all of the books. Not only is this a smart business strategy, it's also a demonstration of foresight few authors possess. This differentiates Sanderson from others. As a result, he's in a league of his own.

And this kind of differentiation is available to any one of us. It's not about authenticity™. Authenticity is a by-product of pursuing one's craft earnestly. It's about integrated effort.

Regardless of what we're creating: essays, videos, podcasts,... If any of these forms touches the frequency-focused world of "content production," it will almost always become episodic, and disconnected. However, if we pursue creating coherent wholes, if we exercise our foresight, we can create something that episodic creators cannot. That's how we escape anything resembling competition.

This is also how we escape the "content treadmill" as others call it. When you integrate pieces together, you have a much higher chance of creating something excellent. Something that stands out. And when something stands out, people talk about it, and share it. The work sells itself by being awesome and different, instead of the author pushing it onto people.

Whole pieces, learning pieces, puzzle pieces

Before you run off to work on your coherent whole work of art, there's an argument to be made for making pieces, episodes, and one-offs. Again, let's take the example of writing.

First, smaller pieces like social media posts or lengthy messages let you get things off your chest. Not all ideas deserve to be a book. No. The sheer number of one-idea, big font, bloated non-fiction "books" attests to this fact. If your interpretation of an idea can be fully articulated in a tweet, fine, it's a tweet. If it's a blog post, it's a blog post. Nothing wrong with that. The idea should dictate the form, not the other way around. When you capture an idea fully, regardless of medium or length, you create a "whole piece" and that can be enough. The End. (Of course, I'd argue that there are probably connections that could be made to your other work, and that, if pursued, could be formed into a series on a topic or a whole new thing.)

Second, pieces are great for creative exploration. If you're doing something new, you probably don't want to make it a part of 35 books. That's too much pressure and creative risk. One-off weird pieces are good for creative experimentation. That's how you explore what you can do.

Third, there is a need to share and sell one's work. Sharing pieces of the whole can be a way to generate anticipation for the main work. Sample chapters, previews, even serialized Substack fiction-those are all valid avenues of, forgive the vulgar term, marketing your own work. The key thing to keep in mind in this case, however, is that the pieces should be like puzzle pieces that are meant to fit into a greater whole. This is different from making just pieces, with no overarching structure.

If you encapsulate a single idea well, then you have a good piece. If you explore something new, then you also have a good piece. If you create a small puzzle piece and share it, that's also a good piece, so long as you have the whole in mind.

However, I'd say people overdo "piece-making" at the moment. Case in point: reaction videos. The vast majority of those videos add absolutely nothing. People just make them because they want to leech off the popularity of the original video. At least compilations are made with some effort, but in the end it's only a slapped-together thing that ends up wasting people's time. In other words, pieces and reactions, even compiled rarely move the consumer. Hence my argument for going beyond one time, quick, episodic creation.

Integrate your pieces, create a masterpiece

At this point, I hope you're on board. You might even consider yourself reformed—now you see that you've been misled by the piece-gobbling machines of social media. But what now, how to make something coherent and whole? Something so awesome that some might call it a masterpiece?

I have some ideas on that. I return to the 3 key elements mentioned above: vision, focus, synthesis.

Vision

Get ambitious. The Pyramids were ambitious. The Sistine Chapel ceiling was ambitious. The Cosmere is ambitious (Sanderson's plan projects he'll finish by the age 74). Now, I'm not saying we all need a 30 year plan. Michelangelo did the ceiling in 4, so that's perhaps a reasonable goal, is it not?

Overall, I think get-popular-quick schemes that the Internet is so inundated with make our vision quite short-sighted. Some excuse it and simply say that to make money you have to run on the content treadmill. That's how the world works. I'm not convinced that's entirely true. I think it's simpler to make money if you sell your soul, certainly, but I believe there are other, more creative ways to do so that can be found through effort and creative exploration.

Besides, you-have-to-make-content-to-make-money is the exact opposite of a vision. It's a mental fog of the worst kind, a "vision" so uninspiring that any artist that starts to believe that will burn out or become cynical precisely because of the lack of masterpieces produced.

Imagine thinking about your work in the last year, or two, or five, and seeing only a sea of content... Isn't that depressing? Crucially, having some sort of long-term vision is also what gives us inspiration in the day to day. It gives us a future target, something to aim towards, whereas the step by step treadmill mantra gets tiring without knowing where you're going. What if you're on the treadmill stuck in a dark musty basement?

I think every artist yearns to create masterpieces, something bigger than the sum of its parts, something daring. Those are the works we can proudly show off to others, and feel good knowing that it was our effort that made it possible.

With that in mind, I challenge you to think longer term. What is your ambitious whole? Now, perhaps you're so used to thinking in days or weeks at most that you're not used to looking farther into the distance of years. Do so. Imagine. Think of something daring, something you could be proud of. Given your artistic abilities and the ideas you want to express, what might a masterpiece look like?

Wanna know a secret? The vision doesn't have to be that original. For example, I know that I want this essay to be a part of a book that I want to sit on my shelf. This is not an original idea. This is directly taken from my Internet friend, Thomas J Bevan, whose book of essays I recently bought. I enjoy taking that book, flipping to an interesting essay and reading it. So I stole his vision. Sue me, Tom. (He won't, too much hassle.) In any case, this can be the good side of a mimetic competition.

Focus

Creating a coherent whole also requires focus. Both daily and long-term. Without focus, a vision is a daydream that will fade into a mildly pained nostalgia of what could have been.

Focus, Vita, we're talking about focus. Funnily enough, the meaning of that word is quite diffuse nowadays. Let's define it in the context of this essay.

Let's start with the long-term focus, since it's the basis for short-term focus.

Availability as a foundation for focus

The information available to us through our long-term and short-term memory serves as a basis for our thoughts and actions. If our mind is full of task-relevant information, then we have a strong foundation of data we can avail ourselves of and we'll almost certainly act regarding the task on our mind.

However, if the only information available to us is a hundred random messages, a hundred TikTok videos, and a hundred tweets, what do we do? There is no coherence to the consumed information. It's worse than a blank slate. Hypothetically, there are three hundred actions we could take. This doesn't create resonance, this creates dissonance of the worst kind. No wonder people feel "distracted."

So, in order to focus on creating coherent works, we need to keep the context for each work available in our mind. The metaphor of the iceberg could be applied to this. The 90% of creativity is keeping the information related to the project top-of-mind, and the 10% is actually the part when we sit down and create. The better we are at gathering that context and keeping it available in our memory, the less time we need to actually get into the zone and make progress.

I'm reminded of this quote:

“You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state.

—Richard Feynman

Lamentably, we now consume more information than ever before. As a result, few of us keep a dozen problems in mind. To me, it seems that I keep maybe three or four on a good day.

So while we don't typically think about our memory when we think about focus, I think it's vital to fill the mind with relevant information, and crucially, to stop the flood of randomness that can displace our own ideas regarding a particular complex piece. It's about the exclusion of the incoherent, so that the mind can't help but focus on the coherent. Viewed from this perspective, the news, social media, or TV even are not harmless. The random facts one learns there that seem harmless are in fact wiping one's working memory clear of information that might have been related to a particular problem. The subconscious mind then doesn't have the right puzzle pieces to solve a particular problem, it has a variety of jumbled puzzles that don't make up an image.

Attention span

Now this refers to the usual idea of focus: you put your head down and work, click, type, lean back and think, click, type, perhaps draw,... the usual.

You may have heard the goldfish 8 second statistic. Supposedly, the normal person nowadays has an attention of about 8 seconds, the same as a goldfish. I don't think it's quite that bleak, but I definitely do think that the number of people who can pay undivided attention to a single task for 30 minutes or more is getting smaller.

This is a problem, because the more complex a whole, the longer attention span is typically required to make progress. And complexity usually adds up over time.

For example, when I'm just starting with a coding project and have it planned out, then the first stage is about creating the individual components and functions. Each basic component and each function can constitute one session of focus. That's not so taxing, mentally. However, once I get beyond the level of components, I need to deal with the complex interactions of those functions and components and match them against the user experience I want to create. And that's where it gets finicky, and that's where it can take 30 minutes just to figure out the first change that you want to make. In those circumstances, a 5 minute attention span (and tolerance-for-boredom span) means that I effectively won't be able to make progress.

I've written about getting better at focusing elsewhere, so I won't go into much more detail. The simplified version is: go as long as you can before you switch tasks, as often as you can. Get into a flow state if possible. There is no magic pill for this, though caffeine (perhaps with a 200mg L-theanine pill) can certainly help.

Onwards to the last piece of the puzzle.

Synthesis

Writer Chuck Palahniuk makes a curious distinction. For him, writing is talking to people, telling anecdotes and assessing people's reactions, making observations and jotting them down into his notebook, or getting feedback on ideas from fellow authors. That's what he calls writing. You might be asking: if that's writing, what does he call sitting at his computer, typing? Keyboarding. And keyboarding is the very last part of the process that he likes to do on planes, preferably.

To me, this is an example of the art of synthesis. This part of the process is often overlooked, precisely because it's harder to categorize as "work" than seeing a person hunched over a keyboard.

To give you a concrete example, one of the things I do is coding. When I'm at the conceptual stage and I'm creating the basic components, I don't need anything. I dive straight into code. However, when the interface is almost ready and I'm hunting for the small adjustments that turn a piece into a part of the whole, diving straight into code (aka keyboarding) is not helpful. If I do that, I end up looking at the code, not knowing what I'm supposed to type. One of my solutions to this? Stare at it. I quite literally open the right screen, and I stare at it. I examine each component and think about it. And gradually, the changes I need to make become clear. I begin to see the connections between the components. The integrations that need to happen. Then I note them down. Once I've stared long enough, then I go keyboard. I mean code. Staring at stuff is a good synthesizing activity. While to an outside observer me, just looking at the code, may not seem like "productivity", it's absolutely integral.

If you stare at a collection of parts long enough, you'll start to see connections. Of course, staring is but one way to synthesize information and figure out what you want to create (form a vision). You can also walk, journal, talk with others, tinker, analyze data... and so on. Anything that helps you piece things together is good.

One thing I'd avoid, however, is seeking more information that is not directly relevant to your work. 8 ways to do this, 15 tricks to do that—Stop! More information equals more pieces to put together, and most people already have too many pieces as it is. Yes, occasional browsing and careless consumption can be fun, but it should come after you've solidified your direction for the near future.

Create your masterpiece

It's not in my nature to leave you without something to apply, a call to action as some call it.

If you're like me, then you've already made a lot of different pieces, across platforms. And it's all fragmented. It's all loose collections of loose collections, of pieces of content of various quality. There's little to point to and say: "Look, I made this and I'm proud of it."

So take a look at your work so far, published or unpublished. What whole could be composed of it? What vision would it make sense to pursue? What masterpiece do you want to make? A book of essays? A series of novels? A movie? An app? An art exhibition? What is an ambitious, awesome thing that you can put together? A whole that is greater than the sum of the parts? A masterpiece that will set you apart from the content-driven competition?

What information do you need to keep available in your mind, so that you can make progress on even a complex whole with ease?

And, finally, what are the synthesizing activities to engage in to see the connections between the individual pieces and realize your vision? Staring? Walking? Talking?

Those are some questions for you, my creative reader. And I also have an ask.

In a world of pieces...

Create a masterpiece.